All images copyright © inherit earth

All images copyright © inherit earth

What are the ‘Volcanic Plains’?

These flat to undulating plains extend from the west and north of Melbourne more than 300 kilometres west, past the town of Hamilton, to Ararat in the north and Colac in the south and cover about 10% of Victoria.

Alternatively known as grasslands, flowerlands or even herblands the plains are characterised by large open areas of grasslands, small patches of open woodlands, stony rises (small rocky hills), volcanic cones, and many permanent and temporary shallow lakes and wetlands. The plains lie mainly on basalt rock and basalt clay soils produced from the volcanic larva flows and ash, and are very new by geological standards, having been laid down between five million to as recently as ten thousand years ago.

All areas on earth have unique and distinctive groups of native plants and animals that have evolved in relationship with each other and the landscape they are part of. The plains to the west of Melbourne have their own unique ecosystems and biodiversity. The flat and fertile appearance of the plains attracted the attention of early European explorers in the 19th Century, such as John Batman and Major Thomas Mitchell, who both described the plains as having the best pasture for sheep ever seen.

Sheep and cattle raising and cropping are now the main occupations on this land today.

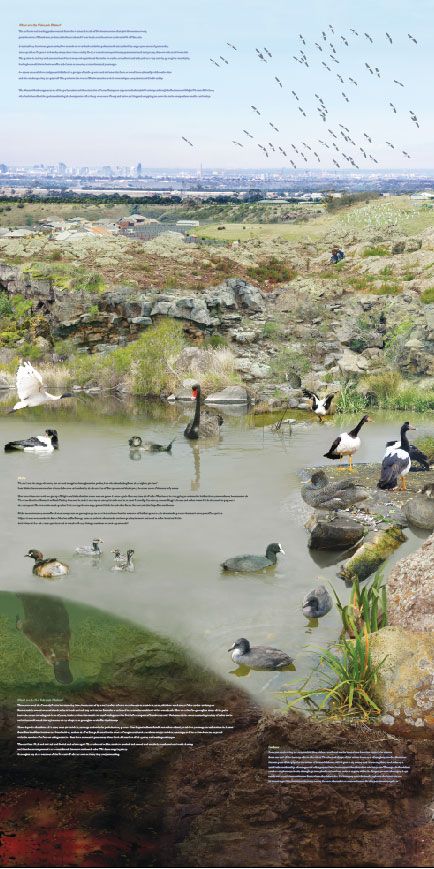

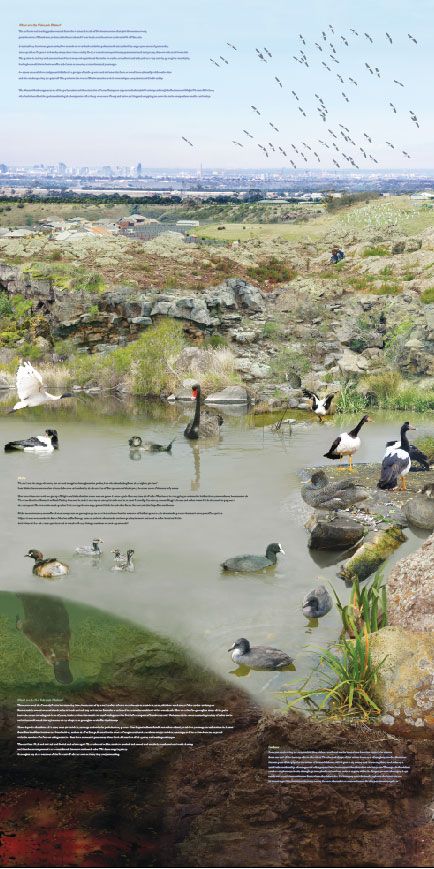

Birds

There is no shortage of crows, ravens and magpies throughout the plains, but what is missing from the original picture? Fewer birds than mammals have been driven to extinction by the incursion of Europeans and their pets, because most of them can fly away.

However there was a whole group of flightless birds that have now almost gone. A small quail-like creature, the Plains Wanderer, is struggling to exist as its habitat has systematically been removed. The once familiar Bustard or Bush Turkey has also been driven out, or eaten, but still can be seen at Serendip Sanctuary, as can Magpie Geese and other water birds that used to populate the once plentiful wetlands on the plains. Other long-absent large ground birds include the Stone Curlew and the Cape Barren Goose. Birds are not usually as confined to an ecosystem or geological place as other animals but the removal of habitat generally is threatening even robust and once plentiful species. Of particular concern is the fate of the beautiful Brolga, once seen in the thousands on these plains, but now reduced to a few hundred birds. And where did all the emus go that used to wander freely in huge numbers over the grasslands?

What made the Volcanic Plains?

These are called the Volcanic Plains because they have been created by a series of lava flows over the last two million years, which covered most of the earlier landscapes.

Basalt rock is cooled lava and the dominant black and red clay soils come from the weathered basalt rocks combined with volcanic ash. However the full geological story of the plain is an adventure covering millions of years, back to when the continent was floating near the South Pole as part of Gondwanaland. Underneath the lava an amazing variety of other rocks and minerals formed through nearly every chapter or geological era in Earth’s history.

Shale deposits that formed in early seas 400 million years ago underlie the plain in many places. Coal deposits from fern forests that existed 50 million years ago stretch under the basalt from Bacchus Marsh to Altona. Granite hills, such as the You Yangs, formed in the ovens of magma under the earths crust 350 million years ago, and have since become exposed with the erosion of softer covering material. Seas have come and gone many times in the formation of the gently undulating landscape. The land has lifted and twisted and folded and submerged. The rocks and sediments have cooked and cooled and cracked, weathered and washed away, and then been compressed or re-constituted into new rocks and soils. This is an ongoing story. Geologists say the volcanoes of the Volcanic Plains are not extinct, they are just resting.

Lichens

So common that they are almost invisible, lichens are found on the basalt boulders that seem to be strewn from one end of the basalt plains to the other. The size and shape of the stones is a result of rough crystalline fractures that are part of the physical structure of basalt. Lichens, which grow very slowly and live a long time, are basically a symbiotic relationship of an algae and a fungus, and have been around for about 600 million years.

The algae in the lichen carries out photosynthesis, changing atmospheric carbon into carbon sugars, while the fungus protects the algae, helps retain water and draws minerals from where the lichen sits. Lichens play a role in breaking down the basalt stones by releasing acidic chemicals that very slowly dissolve the rock to release minerals for the plant’s consumption.